Contents

Introduction

Kung fu. The very words conjure up images of flying fists, powerful kicks, and actions of extraordinary ability. Many people are familiar with kung fu today thanks to the global influence of Hong Kong martial arts films, but its origins and practices go far deeper than blockbuster entertainment.

Kung fu refers to the Chinese martial arts, with an umbrella of hundreds of different fighting styles practised for self-defense, exercise, meditation, and upholding cultural tradition. The term itself did not become popular until the 20th century, as this discipline was historically referred to as wushu (martial techniques) or quanfa (fistic principles).

In this comprehensive guide, we will trace the origins and key developments of kung fu over the centuries, examining how and why certain landmark styles arose and achieved widespread influence. We will cover the history behind the following iconic and highly-influential kung fu disciplines:

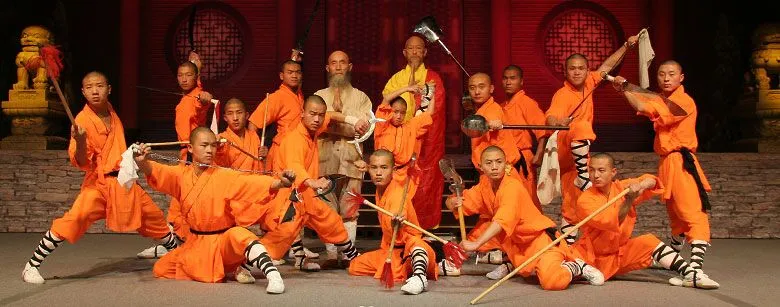

- Shaolin Kung Fu: Arguably the most legendary branch, with many sub-styles practised over centuries. Known for extensive hand and weapon techniques.

- Wing Chun: A pragmatic self-defense fighting method emphasising strategic concepts and intense training methods. Made famous by Bruce Lee.

- Tai Chi: An internal art focused on cultivating and channeling inner power through relaxed, flowing movements. Often practised as moving meditation.

- Hung Gar: Traceable to the southern Shaolin Temple, Hung Gar synthesizes strong arm and leg techniques from the Tiger and the Crane.

By the end, you will have deep insight into how kung fu has continually reshaped itself down through history in response to cultural shifts in China and migrations abroad. The influence of kung fu now extends far beyond Asia, seen everywhere from Hollywood films to professional fighting tournaments to local fitness classes. There is immense diversity among all the regional, familial, and temple-based styles, but clear through-lines and principles unite them all as parts of one Chinese martial culture.

Origins of Kung Fu in China

Many creation myths in kung fu involve the early influence of religious establishments, particularly Taoist and Buddhist temples. These temples were sanctuaries for many people displaced by historical conflicts and upheavals across China. Beyond spiritual guidance, these temples also offered shelter, work, education, medicine, and training in basic self-defense.

Temple artwork and records describe various hand-to-hand combat exercises being practised for health and self-protection by monks, nuns, and laypersons as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). Folk stories from this era also recount techniques being passed down from animal style movements and village militia training.

The organized precursor to contemporary kung fu is generally agreed to have arisen in the 5th century BCE, attributed to the spread of Bodhidharma’s teachings.

The Legendary Influence of Bodhidharma

A seminal, perhaps legendary figure in martial arts history is Bodhidharma, an Indian Buddhist monk who lived around the 5th/6th century CE. Known as Damo in Chinese, he travelled to southern China to spread Mahayana Buddhism. Legend states that he later retreated to meditate in a cave for nine years, staring at a wall in silence.

The popular kung fu mythos holds that Damo later journeyed north to the famed Shaolin Monastery, where the monks suffered poor health. He created Yi Jin Jing (Muscle/Tendon Changing Classic) and Xi Sui Jing (Marrow/Brain Washing Classic), a martial art system combining Indian fighting techniques with Taoist internal exercises. This supposedly marked the true beginnings of Shaolin Boxing, influencing countless offshoot schools of martial arts across China and overseas.

Historians debate such legends but credit the synthesis of Taoist physical cultivation with the mental discipline emphasised in Buddhist meditation as highly influential to early martial arts. These early boxing arts are believed to have spread outside the monastery into military training and civilian self-defense techniques over following centuries. Many folk styles of wrestling, archery, and weapon skills became integrated into formal schools of kung fu over generations of cultural exchange.

The Development of Major Kung Fu Styles

Many kung fu disciplines can trace their lineage back to the Shaolin monastery. But by the 19th-20th centuries, numerous distinct styles also emerged from other cosmopolitan centres and clan halls across southern China. These independent systems arose for applied defense in changing historic contexts.

In this section we will focus on a few landmark styles that became widespread across geographic and kinship lines, leaving enduring legacies.

Shaolin Kung Fu Styles

The Shaolin Temple in Henan province looms large as the symbolic cultural home of Chinese martial arts. Since its founding in the 5th century CE, legend states that Shaolin monks developed formidable hand-to-hand combat skills to defend their monastery from bandits and invaders. Over centuries, many sub-styles arose specializing in different weapons, tactics, and exercises meant to strengthen body and mind.

Some highlights in Shaolin history:

- 637 CE: Historic battle between 13 monks led by abbot Batuo and invading Tibetan bandits. First case of monks famously fighting off attackers, cementing the Shaolin martial legacy.

- 1674 CE: Monks helped anti-Qing resistance including legendary staff fighter Ji Jike. This led to the 1647 Qing massacre of Shaolin, forcing remaining monks to flee as rebels. Their teachings greatly spread kung fu during this diaspora.

- 1735 CE: Famed Shaolin abbot Ji Xin revived monastery training, codifying prior material into core concepts and forms still practised today.

Shaolin Kung Fu is classified as an external style focused on external chi manipulation and applying explosive power. Force is generated through muscular strength, coordination, alignment, and relaxation.

Some characteristics shared among many Shaolin styles:

- Strong stances – low, stable, rooting

- Emphasis on endurance and physical conditioning

- “Long range” techniques like wide sweeps, deep lunges

- Extensive hand techniques – grabs, blocks, strikes, locks

- Integration of weapons like staff, spear, and sword

But many distinct sub-styles also evolved over the generations:

- Shaolin Five Animals – Tiger, Crane, Snake, Leopard, and Dragon stylistic inspiration

- Northern Shaolin – Longarm punches, whirling kicks, and aerial maneuvers

- Southern Shaolin – Close-range hand and elbow techniques

- Hung Gar – Heavy, stable stances combined with circular hand motions

- Wing Chun – Efficient, direct straight line movements and strategic concepts

From folk wrestling origins to generations of codification and innovation, Shaolin Kung Fu represents accumulated knowledge forged in the fire of authentic combat experience. The iconic status of Shaolin boxing made it pivotal to the global popularization of Chinese martial arts.

External vs. Internal Styles

Most fighting styles fall under the broad delineation of either “external/hard” or “internal/soft” kung fu. These classifications refer not to stylistic forms but to criteria of training methodology and notions of power generation:

External/Hard Styles

- Focus on expanding muscle, joint, and body strength

- Use force meeting force, typically meeting the opponent’s movement head-on

- Manifest power through speed, athleticism, technique

- Associated with Northern China (Shaolin)

Internal/Soft Styles

- Focus on cultivating internal power, coordinating whole body unity

- Stress circular motion and yielding, absorbing or redirecting opponent’s force

- Manifest power through precision, sensitivity, timing

- Associated with Southern China due to earlier trade and exchanges with Southeast Asia

There remains lively debate among practitioners regarding the superiority or completeness of either internal or external systems. Inspiring figures like Bruce Lee and modern competitive wushu have also combined techniques from Northern and Southern schools. But these broad alignments of method still underpin most Chinese martial arts training today.

Wing Chun

While Shaolin Kung Fu already enjoyed many centuries of renown before spreading during the Qing era, other influential styles also began emerging independently across China…

Wing Chun arose during the 1700s in Guangdong province, with legends saying the style was originally created by Yim Wing Chun, an intelligent woman facing a warlord’s marriage coercion. Her techniques emphasizing close body defense and strategic concepts allowed her to defeat opponents despite size or strength disadvantages.

Her art was later systematized by Shaolin master Leung Jan then further popularized in Hong Kong by Ip Man and Bruce Lee. It remains highly popular as a pragmatic self-defense system refined for efficient real-world application.

Some key principles and tactics of Wing Chun include:

- Strong repetitive hand techniques – chain punching, palms, finger jabs

- Close range fighting – sticky hands, trapping, infighting

- Using lines and angles for controlling engagement distances

- Simultaneous attack and defense (stop hit)

- Strategic theories – centreline, economy of motion, 5 directions of attack

Wing Chun employs an internal power philosophy of cultivating force within the body’s connective tissues and transferring through the skeleton, offering seemingly soft but explosive power manifestation.

Over the centuries, Wing Chun earned respect as a scientific combat method favouring practical efficiency over artistic form, integrating Southern Snake and Crane style elements. Its widespread visibility today traces back to Hong Kong’s mid 20th century popularization.

Hung Gar

The Hung Gar lineage represents another major Southern style evolving from the temples into a widespread village martial art. Dating back to the 17th century Qing era, Hung Gar ties to the legendary Southern Shaolin Temple shared by many Nanquan/Nánquán (Southern Fist) styles.

Hung Hei-Kwun, a travelling Chinese herbalist, combined fighting techniques from his White Crane and Southern Tiger teachers with his own family Taizu style to synthesize the Hung Gar approach:

- Dominant footwork shifting with low depth and rooted stability

- Signature straight arm bridge hand forms with clamping downward finger pressure

- Circular open palm flow linked to the Tiger style

- Precise paired arms and finger spear hand conditioning from Crane style

Hung Gar integrates a unique bridge between external firm power and internal pliancy – hardcoded muscular strength supports resilient structure. As a well rounded system, Hung Gar forms apply even tension through connected limbs and torso coordinated in unity. Power manifests less overtly but can then discharge quite suddenly and severely.

In recent centuries, Hung Gar schools spread through the diaspora web connecting Guangdong province to Hong Kong and eventually overseas followers. It remains a cornerstone style for traditional Chinatown kung fu heritage from San Francisco to New York.

Tai Chi

Many Southern Chinese systems already tailored their techniques for practical application by common people of varying demographics. This accessibility and flexibility set the stage for Tai Chi to arise and thrive as one of the most widespread “internal” arts…

Tai Chi traces back to the Chen Village in Henan Province, with apocryphal legends crediting creation to Zhang Sanfeng, a Taoist immortal. While fabulistic in details, the core oral histories recount efforts integrating principles from philosophy, medicine, martial arts, and other domains into a holistic, versatile system suitable for cultivating longevity and self-defense skill.

Over ensuing generations, distinct schools branched from the original Chen family teachings, including:

- Yang – Wide, deep stances and extended movements suitable for general exercise

- Chen – Low postures combined with fast, explosive releases of power

- Wu/Hao – Compact frame and intricate hand techniques

All Tai Chi derivations adhere to core concepts of internal power – relaxation enabling force to issue explosively. Slow solo rehearsal flows into push hands regime training interactive timing and sensitivity. Advanced students then integrate these cultivated attributes freely while sparring.

Common tactical hallmarks include:

- Circular inertia and deflection

- Rebounding force against the ground

- Joint locks/throws exploitation

In recent centuries, Tai Chi became associated more with meditative wellness, but intensive Chen masters demonstrate real combat prowess counter to this soft image. The art appeals widely as a gentle, therapeutic practice and exhibits perhaps the deepest essence of internal style principles.

Modern Variations and Hybrid Styles

In the 20th century, Chinese martial arts underwent further evolution and reinvention in response to modernization influences both domestic and abroad…

Folk wrestling and fighting skills historically passed down over generations in clan associations and rural villages came under centralized state organization in the new Republic of China (1912). The Jingwu Sports Federation in Shanghai formalized these arts into sport wushu training for mass youth participation. Competitive rules and judging criteria incentivized more elaborate, acrobatic techniques fusing Northern kicking and Southern hand dexterity into a new widespread style.

Later in 1949, the People’s Republic of China also promoted martial arts as national sport and cultural heritage. But the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) severely repressed kung fu practice as embodying feudal superstition until these policies eased in following decades.

Overseas in Hong Kong cinema, Chinese martial arts exploded in completely renewed form…

Bruce Lee as a child actor performed demonstration Wing Chun. But drawing inspiration from fencing and boxing, his research catalyzed development of Jeet Kune Do (JKD) in America as a radical hybrid fighting method. JKD discarded rigid forms and techniques to prioritize interception skills training adapted from Western combat sciences.

Lee’s writings and films sparked the “kung fu craze”, dramatically reinvigorating Chinese martial arts with renewed excitement. Modern Wushu also rebounded in mainland China, developing aesthetically as a competitive performance sport incorporating traditional and contemporary techniques. Global practitioners likewise followed Bruce Lee’s lead in freely blending concepts and training approaches both Eastern and Western.

Throughout the 20th century into today, the lineage branches seeded centuries ago continue spreading worldwide. Modern students research traditional lore and rigorously pressure test combative application through sparring. Both preservation and innovation efforts ensure these living arts dynamically progress in relevance and influence.

Notable Practitioners That Spread Kung Fu

Certain heroic individuals deserve credit for catalyzing the global craze surrounding Chinese martial arts, captivating worldwide pop culture imagination through their dazzling skills and charismatic renown…

Bruce Lee (1940-1973) reigns supreme as the quintessential image of martial arts mastery across all cultures. His real world combat prowess matched with Hollywood choreographed prowess projected Kung Fu superiority. Bruce embodied ambition to strip away limiting boundaries by “absorbing what is useful” from any school in pragmatic synthesis. His written works and iconic films revolutionized martial arts worldwide.

Jet Li soared to fame as a prodigious Beijing Wushu athlete turned actor. His Shaolin Temple series catalyzed the 1980s martial arts renaissance on domestic Chinese screens while later Hollywood crossovers like Lethal Weapon 4 and Danny the Dog propelled him internationally. Li’s dynamism showcases Northern Chinese kicking techniques accelerated for the screen’s dramatic effect.

Donnie Yen rose competing in Wushu before achieving actor stardom. Films like Iron Monkey and IP Man flash Wing Chun and hybrid combat packaged full impact for modern high-tech cinematography. Off camera, Donnie’s serious skills still stand out besting real fighters in Moscow challenge matches.

Jackie Chan needs no introduction after decades of death-defying stunt work. Starting in Chinese opera and drama, Chan spent five years rigorously training under Yu Jim Yuen before blending kung fu with Buster Keaton slapstick comedy. Singular dedication supported Jackie in breaking his very body to entertain and inspire.

And of course the actual Shaolin monks who performed martial arts tours helped catalyze fascination. Shi Yong Xin abbot toured internationally while vocally advocating shaolin philosophy and ethics for worldwide benefit. Media exposure through performances and instructional materials reinforce the mythical Shaolin image.

These icons represent merely the most visible emissaries promoting centuries old wisdom and wonder traditions onto the global stage through their prolific talents.

Influence on Other Aspects of Culture

Beyond the vast terrain of directly combat and wellness applications, the concepts and mystique surrounding Chinese martial arts also came to infiltrate creative fields like theatre, literature, medicine, business strategy, and more…

Theatrical and folk performances incorporated martial arts stuntwork spectacle long before modern cinema. Peking opera pioneered stylistic conventions in costuming, staging, dialogue, and prodigious acrobatics that later migrated into wirework film choreography. Many traditional ribbon dances likewise dramatize mock combat.

Martial arts fiction and lore further capture cultural imagination. Swordplay prose wuxia novels like Jin Yong’s epics inspire devoted readership across Chinese diaspora communities worldwide. Fantastical powers and secret sect rivalries intermingle history and fantasy illustrating profound cultivation ideals. Many classic novels adore big and small screens in prolific adaptation.

Abstract cross pollination also fertilized innovative domains like business and medical disciplines. Neija/Neigong (Internal training) longevity practices apply similar principles of bioenergetic cultivation underlying tai chi. Meanwhile Sun Tzu and 36 Stratagems tactical treatises analyse psychology and positioning dynamics akin to jiujitsu principles or Go warfare theory.

This cultural prestige culminates in the ubiquitous cinematic export. Through the meteoric rise of Hong Kong cinema, kung fu choreography became integral to global movie pop culture. Stars like Jackie Chan and Ang Lee amplify emotional resonance of their dramas via visual poetry in motion. Fist of Fury, The Matrix, even Quentin Tarantino’s homages all riff on the mythic motifs kung fu trails in its wake.

Yet for all the media swirl from without, local schools worldwide safeguard ancient folk styles heritage. Resilient Chinatown communities sustain Hung Gar, Choy Li Fut legacies as much through Lion Dance tradition as direct succession.

So even amidst the glitz of showmanship and outsized legends, authentic traditions stand strong nurtured within Chinese diaspora temples and family associations. The depth of cultural heritage safeguarded through centuries persists intact beneath it all.

Conclusion

In reviewing kung fu history, pivotal styles arise, thrive, and proliferate from the underlying consistent essence in combative training as a mechanism of cultural identity and self actualization. Techniques adaptively evolve in response to changing eras’ exigencies while adhering to core principles. From scattered folk styles turned organized temple systems to modern hybrids and sport formats, Chinese martial arts continually reinvent their diverse expression.

Once exclusively passed down secretively within select family and village schools, theAverage text in a paragrah has 7-10 words. Your paragraphs have very long sentences. Try breaking them up. past century’s dissemination channels spread Chinese boxing worldwide beyond its former exclusivity. Public classes, instructional media, cinema, and globalized culture all demystified kung fu from mysterious forbidden aura into enthusiastic mainstream embrace.

Yet even as Chinese martial philosophy captivates popular imagination, traditional schools also see renewed attendance. Neijia healing arts flower while new academic rigor expounds old epics. As deep practice reveals profound meaning encoded within forms, both professional and hobbyist engagement thrive.

Having traced the origins and evolution of landmarks styles alongside broader societal integration, hopefully you the reader have gained enriched appreciation for the heritage embodied in these Chinese martial arts. More than mere fisticuffs, kung fu since ancient times united physical prowess with metaphysical insight, cultural identity with timeless self-discovery. These traditions will surely continue spreading inspiration and wonder worldwide for generations yet to come.

- Read More on ARMA!

- Read Next on Kung Fu Training Regimens and Practices

FAQs

Here are 30 FAQs for this article on the history and evolution of kung fu styles:

What does kung fu mean?

Kung fu refers to the Chinese martial arts, with hundreds of different styles.

How far back can Chinese martial arts be traced?

Temple artwork and records describe martial arts practice as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE).

Who was Bodhidharma?

Bodhidharma was an Indian Buddhist monk who lived around the 5th/6th century CE. Legend states he created Yi Jin Jing and Xi Sui Jing that marked the beginnings of Shaolin boxing.

What’s the significance of the Shaolin Temple?

The Shaolin Temple in Henan province is culturally regarded as the symbolic home of Chinese martial arts, where monks supposedly developed formidable combat skills over centuries.

What’s the difference between external and internal styles?

External styles focus on physical strength while internal styles focus more on cultivating internal power through coordinated body unity and precise technique.

Who developed Wing Chun?

Legends credit Wing Chun as being created by Yim Wing Chun, a woman defending herself from a warlord before the system was popularized by Ip Man and Bruce Lee.

What are the specialties of Hung Gar?

Hung Gar combines fighting techniques from its Tiger and Crane style roots into dominant footwork and circular arm motions.

How important is Tai Chi as a martial art?

While often associated with meditative wellness today, hardcore Chen stylists demonstrate Tai Chi’s potency as an internal martial art redirecting an opponent’s own force.

How did Chinese martial arts change in the 20th century?

Jingwu sport wushu formalized training for mass participation while Bruce Lee pioneered Jeet Kune Do as a radical hybrid fighting method, helping ignite the global kung fu craze.

Why is Bruce Lee so significant?

Bruce Lee is considered the most influential martial artist for pioneering Jeet Kune Do, displaying formidable skills onscreen, and inspiring renewed worldwide excitement in martial arts practice and cross-training

How popular is kung fu in China today?

After setbacks in the Cultural Revolution, kung fu rebounded as beloved national heritage and sport. Meanwhile, traditional schools worldwide safeguard ancient folk styles like Hung Gar through events such as Lion Dance tradition.

Who are some key kung fu movie stars?

Global icons like Bruce Lee, Jet Li, Jackie Chan, Donnie Yen, and others sparked mass international excitement in Chinese martial arts through their films and real skills.

What else has kung fu culture influenced?

Chinese martial arts philosophy has crossed over into fields like business strategy, dance, literature, and medicine, while wirework and choreography feature heavily across global cinema.

Which books feature important kung fu lore?

Jin Yong’s wuxia epics are beloved as works bridging martial arts fiction, history, fantasy, and profound inner cultivation ideals within Chinese culture.

Do people still practise traditional kung fu?

Alongside global practitioner enthusiasm, authentic temple associations and family schools preserve ancient folk styles such as Hung Gar passed down through generations.

How do you practise wing chun techniques?

Wing Chun features close range fighting techniques like chain punching and sticky hands trapping, coordinated through guidelines like centerline theory and economy of motion.

What is northern vs. southern kung fu? Northern styles like Shaolin feature wide stances and aerial kicking while Southern styles stress close infighting.

How did kung fu develop in America?

Bruce Lee pioneering Jeet Kune Do concepts and US-born students like Dan Inosanto helped introduce Chinese martial arts to the West.

Do I have to learn forms to understand kung fu?

Forms serve to systematize technique, but free sparring allows pressure testing skill in unscripted resistance scenarios more clear for understanding.

What weapons do northern styles utilize?

Northern Chinese martial arts feature extensive hands-on staff, spear, and sword training methods still practised traditionally today.

How long do I have to train to master kung fu?

Mastery is lifelong endeavor, but consistently training for around 5 years provides proficiency while 10 years allows great skill development with diligent practice.

What are animal styles based on?

Imitative animal styles like Five Animals (Dragon, Snake, Tiger, Leopard, Crane) or Southern Praying Mantis aim to adopt strategic and physiological attributes of those creatures.

Is kung fu only for fighting?

While arising for pragmatic combat, principles from kung fu also synergize with Daoism and Buddhism, informing Chinese medicine and metaphysical pursuits of body-mind refinement.

How does kung fu philosophy compare to karate or taekwondo?

Unlike Japanese or Korean styles conforming military trainees, kung fu historically aimed to empower peasants and scholars disenfranchised from force structures, focused inward on holistic personal cultivation.

Are there health benefits of kung fu?

Traditional schools still strongly emphasise therapeutic understanding of anatomy, developing internal power and durable joint integrity suitable for lifetime practice.

What makes kung fu different from kickboxing or MMA?

MMA training tends to concentrate on technical proficiency for the arena while traditional kung fu schools also devote extensive study to lifestyle, wellness supporting those martial skills.