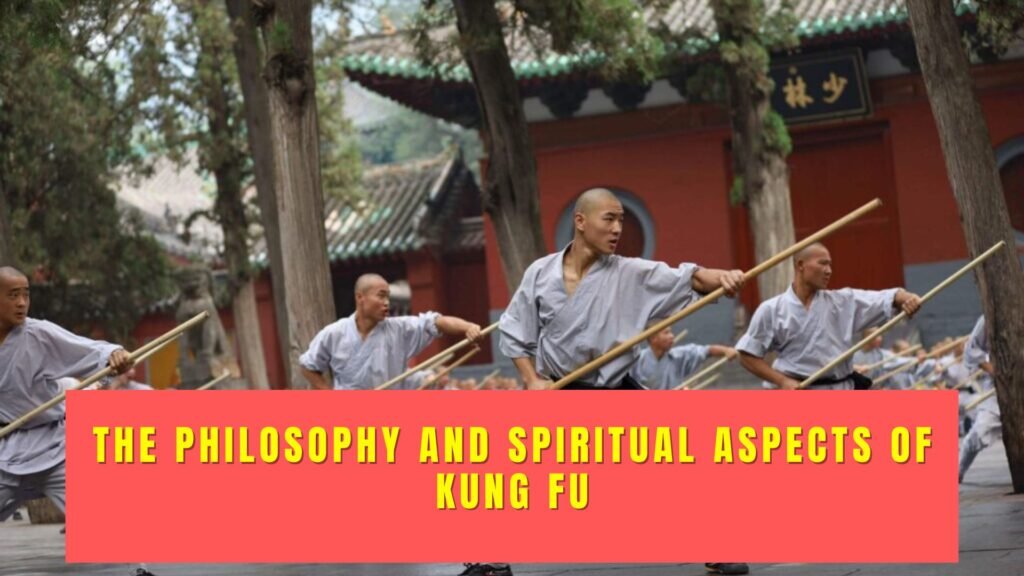

Kung fu. The legendary Chinese martial arts that utilize mystical concepts of Qi power. Black belts breaking stones and wooden boards with their bare hands or flying kicks. Shaolin warrior monks with shaved heads and orange robes training relentlessly. This is the exciting image of kung fu etched in popular imagination.

But there is far more philosophical depth to authentic kung fu than most people realize. Beyond the physically demanding training, traditional kung fu integrates elements of Qi (Chi) cultivation, yin-yang principles, meditation, Chinese medicine, and ethics. Understanding these integral spiritual aspects provides a window into the holistic personal cultivation at the heart of kung fu.

This guide will unpack the key philosophical ideas within kung fu stemming from Taoism, Confucianism and Chinese Buddhism. Core concepts around Qi, yin and yang theory, Zen presence of mind and more are still relevant for personal development today. While the lore of legendary kung fu masters with paranormal abilities should be critically examined, consistent diligent training has scientifically validated benefits for mind-body awareness.

Contents

What is Kung Fu?

Kung fu refers to the Chinese martial arts that utilize specific stances and specialized punching, kicking and defensive movements. Well known examples of kung fu include:

- Shaolin Kung Fu: Perhaps the most famous style. Developed by Shaolin monk Bodhidharma at the Shaolin Temple using Zen Buddhist principles. Famed for rigorous conditioning and animal forms like tiger, crane, snake, leopard and dragon.

- Wing Chun: Close-range fighting system focused on rapid punches and tight defense. Made famous by Bruce Lee.

- Tai Chi: Slow, graceful movements focused on cultivating Qi energy and balancing yin-yang. Widely practiced today for health and meditation.

While kung fu does teach fighting techniques, the core purpose is strengthening the body, improving health and developing the mind. Traditional training methods emphasize cultivating Qi (intrinsic life energy), practicing mindfulness in motion, detachment from ego and living harmoniously. These concepts are influenced by the three major Chinese philosophical traditions of Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism.

Importantly, the term kung fu refers more to disciplined skill acquired through steady effort over time. Like saying a master violinist has great “musical kung fu”. When discussing Chinese martial arts, the terms kung fu, gongfu or wushu are often used interchangeably by practitioners today.

History & Development of Kung Fu Philosophy

The seeds of Chinese martial arts date back over 6,000 years ago to self defense techniques during the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties. But much of what is recognized as classical kung fu emerged during the Spring and Autumn Period (771‒476 BC) and Warring States Period (475‒221 BC) when philosophers like Confucius and Lao Tzu proliferated spiritual ideas.

Buddhist Influences

Buddhist concepts began shaping Chinese kung fu most notably through Shaolin Temple during the 5th century AD. The Indian monk Bodhidharma is credited with founding Shaolin quanfa (fist methods) by blending Taoist breathing and yoga exercises with martial techniques to help strengthen the monks.

Core Buddhist values like compassion, mindfulness and detachment from suffering became integral to training the body, breath and mind in unison. The famous northern Shaolin Temple style describes 5 animal forms (dragon, snake, crane, tiger, leopard) representing Buddhist ideals:

| Animal | Buddhist Concept |

|---|---|

| Dragon | Wisdom |

| Snake | Flexibility of mind and body |

| Crane | Grace, precision and alertness |

| Tiger | Inner strength and courage |

| Leopard | Speed and power |

Confucian Virtues

Confucian teachings place importance on hierarchical relationships, ethical discipline, filial piety, rigorous etiquette and becoming junzi – a morally noble superior man. These principles translated into strict teacher-student dynamics and cultivating mental focus alongside physical skill in kung fu:

- Loyalty and courage to master techniques without fear of difficulty or pain

- Righteousness and integrity as critical for advancing ranks

- Propriety, respect, humility and discipline in the training space

Thirteenth century texts like Epitaph for Wang Juye linked martial arts prowess with Confucian virtues like wisdom, trust, responsibility and judgment.

Unifying Concepts of Qi and Yin-Yang

Daoism and folk religion in China traditionally centered on living in harmony with cosmic forces and cultivating Qi vital energy inherent within the body.

The concept of yin and yang complementary opposites balancing universal order also became integral – applying to cycles of time, the body and kung fu strategy. Deflecting hard force with soft flexible response exemplifies yin-yang dynamics.

These concepts coalesced over centuries into holistic frameworks for health later termed Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) – which includes practices like acupuncture, tai chi exercises and herbal medicine.

By the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644AD), diverse kung fu styles with shared philosophical roots had proliferated into established comprehensive systems combining:

- Physical training and conditioning

- Natural health and longevity strategies

- Daoist-inspired meditation

- Martial techniques from battlefield experience

Over successive centuries and waves of migration, these traditional Chinese martial arts spread first throughout Asia and eventually globalized into an international phenomenon through mass media like movies and competitive tournaments. But at the core remains an interwoven system integrating mental, physical and spiritual development.

Qi / Chi Explained

Of the many spiritual aspects found in Chinese kung fu, the concept of Qi or Chi energy is arguably the most integral and mystical idea. Qi underpins principles in traditional Chinese medicine, meditation practices and martial arts strategy.

But unpacking Qi requires first setting aside ingrained assumptions from Western bio-medical science – which largely rejects unseen forces and tends to measure only physical mass and energy systems.

Defining Qi

There is no universally accepted single definition of Qi among scholars and practitioners. Some interpretations include:

- The universal life force or vital energy within all organic and inorganic substances

- The invisible forces of attraction/repulsion (such as magnetism or gravity)

- The flow of matter and energy (such as air and water)

- Inherent potentiality yet to materialize

Rather than a single concrete thing, Qi is better understood as the very basis of change itself – the unseen potential and animating spirit behind all observable phenomena in nature.

Qi Origins

References to qi have existed since pre-historic Chinese oracle bone script (c. 1600 BCE). Qi philosophy evolved over centuries, adopting aspects of Daoist cosmology, classical elements, I Ching hexagrams, Traditional Chinese Medicine and osteopathy among other influences.

Within the human body, Qi was viewed as vital essence distinguished from physical tissue. Master physician Sun Simiao (c. 673 CE) wrote:

If you wish to study treatment, you must first investigate the principles of the qi

So developing ways to cultivate and harness Qi became the foundation of health – giving rise to breathing techniques, tai chi, Qi Gong exercises among other practices to optimize energy flow.

Martial artists in turn synergized these concepts into developing Iron Shirt methods, Dim Mak pressure points and meditative practices to strengthen their combat techniques – drawing parallels between a strong Qi flow with powerful martial capacity.

Perceived Roles of Qi

Within the holistic Chinese medicine framework, having strong & balanced Qi is viewed as essential for:

- Vitality & Longevity

- Stamina & Strength

- Resistance to Disease

- Mental & Emotional Health

- Recovery from Injuries

- Spiritual Development

Those believed to have cultivated high levels of Qi like Shaolin warrior monks and Qigong masters were revered as possessing exceptional abilities – including paranormal feats like telepathy, telekinesis or control over involuntary body processes.

But given the intangible nature of such incredible claims, traditional Chinese medicine still faces ongoing controversy and skepticism from Western scientists who argue placebo effects likely explain anecdotes around Qi rather than any objectively verified mystical energy source. Nonetheless, a growing body of research provides more insights into real observed benefits of mind-body practices – albeit through physiological effects rather than metaphysical ones.

Yin Yang Concept

Closely related to Qi is the concept of Yin and Yang – the interconnected opposites which form the basis of ancient Chinese cosmology. The ubiquitous black and white circle symbol ☯ representing Yin Yang elegantly signifies this key duality found throughout the natural world – such as night and day or winter and summer.

The Yin principle is dark, cold, slow, soft, passive, diffusive, descending and correlative with femininity and the moon. In contrast, Yang embodies warmth, light, activity, hardness, aggression, ascending motion and masculinity linked to the sun. Yin Yang implies mutual conflict but also mutual complementation – one cannot exist without the other, the seed of one exists within the other.

Yin Yang Balance

Importantly, the goal within Chinese philosophy is aligning these ever-changing forces harmoniously rather than having one override the other completely. Being overly aggressive and forceful (excess Yang) or overly passive and inert (excess Yin) are both ultimately harmful states resulting from imbalance. Optimal states manifest when external forces align smoothly with internal dispositions.

Therefore traditional Chinese medicine places importance on assessing deficiencies in Yin or Yang during diagnosis so as to restore organismic balance through treatments like acupuncture, massage, herbalism or physical/mental exercises.

Martial artists apply similar Yin Yang thinking towards strategy and technique – deflecting aggressive force with non-resisting softness while unleashing righteous explosive power and technical precision when appropriate. The legendary Tai Chi symbol of snakes entwined called Taijitu further embodies this dance between supple yielding and unstoppable strength.

Examples in Martial Arts

- Tai Chi: Slow, graceful, dance-like movements cultivating and harmonizing Qi flow in alignment with Yin Yang phases

- Bagua Zhang: Fluid evasive footwork circling opponents to find openings reflecting Yin Yang changes

- Hsing I: Linear explosive power erupting from stillness showcasing Yin transforming into Yang

- Wing Chun: Close-range punches and tight defence neutralizing force with minimal effort demonstrating Yin principles

Therefore in martial arts, deeply knowing Yin and Yang goes beyond simply recognizing the duality itself towards profoundly embodying natural flow states synergizing inner force and external adaptation.

Buddhist Concepts Within Kung Fu

While less overtly emphasized compared to Daoist and Confucian thought, Chinese Buddhism has significantly shaped spiritual dimensions of kung fu – especially regarding mental focus and ethics.

Core Buddhist teachings center on cultivating compassion, letting go of ego/attachments and recognizing the impermanent, suffering nature of ordinary embodied experience. Through practices like meditation, presence and mindfulness, clarity of insight into reality is said to be attained – culminating in states of bliss, fearlessness and non-dual transcendence of apparent separation.

The legendary Shaolin Temple formally integrated such Buddhist pursuits into martial arts training starting in the 5th Century CE under the monk Bodhidharma (known as DaMo in Chinese). While historical details remain contested by scholars, DaMo is credited with synthesizing Indian Buddhist ideas into existing Chinese martial arts – thereby establishing Shaolinquan as the progenitor fighting style inspiring later kung fu schools.

Key Buddhist concepts permeating kung fu culture include:

- Mindfulness – Attention focused on the present moment with non-judgemental awareness as emphasized through meditation

- Presence – Total mental absorption and energetic connection to movements and sensations

- Detachment – Letting go identification with ego, transient thoughts or external phenomena

- Discipline – Strict training and moral self-restraint to overcome base impulses

- Wisdom – Deeper insight into the underlying nature of existence and source of suffering

- Compassion – Universal loving kindness towards all sentient beings to transcend harm

Traditional Shaolin animal styles like Tiger, Crane, Mantis and Monkey Kung Fu integrate martial techniques with core Buddhist virtues and Chan philosophy ideals. The white crane for example represents vigilance – to strike with precision as soon as an opponent creates an opening. Meanwhile the Praying Mantis relies on lightning fastedeak attacks reflecting Buddhist notions of effortless action.

Vegetarianism

In accordance with non-violence precepts, Buddhist kung fu followers often adopted strict plant-based vegetarian or vegan diets described historically as pure eating. This departs markedly from typically omnivorous Chinese cuisine.

The Shaolin Temple notably once prohibited not only meat but also pungent vegetables like garlic or onion – perhaps linked to ancient Indian ascetic traditions – as potentially stimulating aggression, passions or dullness of mind during intensive meditation.

So while not always overtly discussed beyond monastery settings, Buddhist ethics significantly shaped the development of Chinese martial arts alongside better known Daoist and Confucian ideas. Gentleness towards others when able combined with fierce determination against injustice aligns well with commonly attributed Shaolin wisdom – “Steel is not always strong and silk is not always delicate“.

Confucian Concepts Within Kung Fu

Confucian philosophy focuses on cultivating moral excellence, righteousness, etiquette, filial piety and meritocratic governance. Rather than a formal unified belief system or religion per se, it embodies an ancient Chinese moral, political and philosophical tradition steeped in scholarship and ritual propriety.

Core Confucian virtues include:

- Loyalty & Duty

- Integrity & Honesty

- Kindness & Benevolence

- Politeness & Propriety

- Perseverance & Hard Work

These principles carried over significantly into martial arts teacher-student relationships and training hall conduct. Unlike modern commercial gyms, traditional kung fu schools (wǔguǎn) maintain hierarchy, decorum and strict discipline modeled after Confucian disciple cultivation.

Etiquette & Hierarchy

Students bow upon entering and leaving the space. Shoes are removed before stepping onto training floors. Excessive chatter or noise making is prohibited. Younger students defer to senior ranking levels without quarrel. Questions are asked politely. Gratitude towards the master instructor and ancestors theoretically ensures harmony and acceptance from new members.

Mental Discipline

Confucianism emphasizes steadfast focus, hard work and willpower alongside physical technique.Grueling repetition drills toughen limbs to master intricate skills and flowing transitions that evade opponents. Studying old manuscripts, qi manipulation or philosophical concepts often complements combat training – echoing the Confucian emphasis on continual self-cultivation through conscious effort and striving to become junzi, the morally superior gentleman.

Diligent long-term practice aimed at internalizing core principles called gongfu lead towards technical fluidity termed shenfa. In many ways, these dynamics parallel Confucian disciple ideals of sincerely reshaping oneself through embodied wisdom greater than mere intellectual grasp.

So in contrast to modern commercialization of Chinese martial arts either as spectator sport performance or simplified health exercise, traditional kung fu schools retain tight-knit character development reflecting enduring Confucian lineage ethics adapted for warfare contexts.

Taoist Concepts Within Kung Fu

As one of the major historical religious & philosophical traditions indigenous to China, Taoism significantly shaped conceptual understandings around cosmology, longevity practices and the metaphysical aspects of martial arts like Qi manipulation.

Key Taoist Texts

While founded on shamanistic ancient folk religions tied to nature worship and ancestor rituals, Taoism became formalized through a canon of substantial writings – notably the seminal Tao Te Ching attributed to the legendary Lao Tzu (aka Laozi) and the densely allegorical Zhuangzi text named after Zhuang Zhou. These build upon the I Ching – the ancient Chinese divination manual of hexagrams used for fortune telling also inspired by Yin Yang and five elements theories.

Living in Harmony With the Tao

Taoist thought emphasizes living in harmonic alignment with Tao – the generative ontological process behind all existence translating simply as “The Way”. Humans are called to embody the effortless quiet power of water streams cutting through solid rock and the organic strength of bamboo resisting hurricane winds.

Seeking externally derived goals such as fame, wealth or social status are seen as diverging from the natural Tao – inevitably inducing suffering when such transient things inevitably fade. Instead training focus inward to conserve Jing essence, cultivate Qi energy and clarify Shen spirit aligns with the Tao – the subtle inner power embodied by sages who then inspire lasting external changes through non-coercive presence.

Wu Wei

This way of effortless non-doing known as Wu Wei importantly differs from being passive or weak. Adept martial artists exemplify the mindset by calmly receiving force then redirecting attacks in sudden explosive bursts after identifying openings. There is natural dynamic rhythm between tension and relaxation – neither overly stiff like a corpse nor slack like mush. Years of diligent practice allow spontaneous technical flow without consciously thinking through movements or strategies. This embodies the Taoist sacred text passage “The hard and stiff are companions of death while the soft, supple and gentle are expressions of life“.

So from a Taoist lens, the highest level martial artist paradoxically transcends technique altogether when fully immersed in the Tao – fused with cosmic rhythms of Yin Yang change through pure presence beyond identity.

Alchemical Traditions

Various fringe Taoist sects developed elaborate physiological techniques claimed to profoundly transform the body from within through mystical arts like internal alchemy (Neidan 內丹術).

Obscure manuals detail metaphorical internal circulation processes to refine Jing (essence), Qi (vital energy) and Shen (spirit) – thereby reportedly attaining supernatural powers (altering weather conditions or transmuting base metals to gold) and even pursuits of corporeal immortality.

But most historians regard such goals as speculative allegory rather than physically achievable states. Nonetheless, determined adherence to associated demanding regiments emphasize regulating diet, advanced visualization, qi circulation and modulating sexual activities to direct attention inwards and master corporeal nature.

So while not as widely known or practiced compared to more prominent Daoist longevity methods like tai chi exercises or qi gong breathing, secret alchemy techniques highlighting intricate energetic control significantly influenced conceptions around the metephysical possibilities of body refinement.

Xian Immortals

Within Daoism, legendary individuals who dedicated themselves to spiritual cultivation practices were said to transcend the ordinary physical form and became ‘immortals’ or ‘Xianren’ (仙人). Reputed abilities of the enlighten Xian include:

- Prolonged lifespan for hundreds or thousands of years

- Teleportation, telekinesis or other psychic powers

- Projection of multiple embodiments or division of consciousness

- Control over involuntary bodily processes

- Alchemical transmutation of substances like base metals into gold

The most well known Xian figure is the ‘First Immortal’ Lu Dongbin (712 CE) – one of the mystical Eight Immortals of traditional lore.

While largely considered legendary today, the legacy of the Xian evolved armies of Taoist priestmonks known as the Thunder Immortals (Leiting Xianren) who historically carried swords and spell-charms to protect against ghosts, demons and black magic. The tradition of occult combat practices from medieval times persists in certain esoteric lineages today- blending elixirs, incantations and martial techniques toward unfathomable ends.

Contemporary Applications

While ancient Chinese culture bears little resemblance to contemporary societies shaped by rapid technological growth and consumer capitalism, the core spiritual concepts around vitalism, consciousness and self-cultivation remain highly relevant for both traditional practitioners and modern secular seekers.

Holistic Health

Traditional Chinese Medicine enjoys a resurgence globally as people recognize limitations of reductionist medical systems to address complex chronic diseases. Integrative practices blending acupuncture, herbs, Daoist breathing/meditation and movement therapies (Tai Chi, Qigong, Kung Fu) empower sustainable wellness models balancing mind, energy and body.

Self-Actualization

Ancient Daoist & Buddhist focus on non-egoic presence and cultivating innate potential resonates in modern human development fields like Zen Coaching or Flow State training popularized by thought leaders such as Dr Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.

Mind-Body Research

While mystical notions of Qi and psychic powers evade scientific proof, empirical health improvements from mindful training are well documented – especially decreased inflammation, stress relief and neuroplasticity. Carefully designed studies measure how kung fu and tai chi meaningfully impact cognition, emotional regulation, proprioception, balance, reaction time and resilience.

So slick media tropes aside, the essence of cultivated wisdom rewarding diligent practice persists from generations of Patient Teachers sharing hard-won skills addressing the perennial human question – how best to live?

Globalization

Ongoing cultural diffusion continues expanding awareness of kung fu worldwide through international exchanges, scholarly discourse, popular media and fusion innovations like the emergent field of Contemplative Sciences synthesizing Western empiricism with Eastern introspective practices.

Increasing appreciation of shared embodied existence may gradually guide humankind’s collective maturation beyond unhealthy obsession with ephemeral division and conflict.

Read Next on Kung Fu for Health and Fitness: Achieving Whole Body Wellness

Conclusion

Kung fu ultimately embodies far more than spectacular physical feats and staged combat performances seen through a Western gaze. Deeper investigation reveals a multidimensional living heritage interweaving physical prowess with holistic therapies alongside self-cultivation practices cultivating ethics synergy and flow awareness.

The common thread integrating myriad styles and lineages remains training presence through moving meditation to realize non-dual liberation from illusion of egoic separation.

Attaining inner peace with fluidity to skillfully serve social harmony.

Optimizing personal health to actualize individual potential that collectively uplifts family, community and our shared world towards sustainable long-term balance. This is the heart of kung fu.

FAQs

Here are 30 frequently asked questions for this blog post on The Philosophy and Spiritual Aspects of Kung Fu:

What is kung fu?

Kung fu refers to the Chinese martial arts that utilize specific stances and movements for attack and defense, as well as cultivate mind, body and spirit.

Is kung fu just about fighting?

No, traditional kung fu practice is a holistic mind-body training integrating physical conditioning, self-defense skills, and Daoist-inspired practices for cultivating wellbeing and self-realization.

What are the main styles of kung fu?

Major styles include Shaolin Kung Fu, Wing Chun, Tai Chi, Baguazhang, Xing Yi and Praying Mantis, among dozens of unique regional styles. Each have specific techniques and philosophical characteristics.

When did kung fu originate?

The foundations of Chinese martial arts date back over 6,000 years but classical kung fu coalesced between the Spring & Autumn period (771‒476 BCE) and Ming Dynasty era (1368-1644 AD) integrating diverse influences.

What does kung fu mean?

The term kung fu refers more to disciplined skill acquired through steady effort overtime rather than specifically martial arts. Like having great skill at playing music or cooking.

How has religion influenced kung fu?

Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism have extensively shaped the spiritual dimensions of kung fu philosophy and training methodology over centuries.

What does Qi mean?

Qi (chi) refers to intrinsic vital energy within the body according to traditional Chinese medicine. It is cultivated through exercises, meditation, diet and martial arts.

What does Yin and Yang mean?

Yin and yang represent complementary opposites (dark/light, female/male, cold/hot etc) that balance each other in nature and human health. Neither can exist without the other.

How does Buddhism inspire kung fu?

Concepts like mindfulness, meditation, virtue, non-harm, wisdom and detachment from ego are emphasized in Buddhist inspired kung fu to train consciousness alongside physical fighting ability.

What are the core Confucian virtues

Loyalty, duty, integrity, kindness, propriety, filial piety and perseverance shape the mental discipline and hierarchy within traditional kung fu school culture.

What Daoist text is most important?

The seminal Tao Te Ching attributed to sage Lao Tzu explains core principles like wu wei, aligning oneself with the generative ontological Tao and embodying supple strength.

How does Tai Chi exemplify Daoism?

Slow mindful movements emphasizing softness, redirection of force and Qi cultivation epitomize core Daoist principles applied through an embodied moving meditation.

Were there really kung fu monks with magical powers?

Legends of Shaolin warrior monks display superhuman abilities but lack conclusive evidence. Nonetheless, extraordinary capacities from exceptional dedication to any skillset cannot be ruled out.

Is kung fu only for young fit people?

Kung fu training can benefit anyone of any age or fitness level when appropriately adapted to individual capacity. Low impact styles like Tai Chi are especially popular for seniors.

What modern benefits does kung fu offer?

Improved fitness, coordination, proprioception and reaction time. Stress relief and mindfulness. Injury prevention and rehabilitation. Boosted confidence and focused presence.

Does kung fu have competitive fighting?

Yes, Chinese martial arts tournaments featuring either choreographed performances (Taolu) or controlled full-contact matches (Sanda) have become popular internationally.

How long does it take to get good at kung fu?

Consistent diligent training for 3-5 years with an authorized Sifu (master teacher) is generally required to build a solid foundation in any style before skill level can advance steadily.

What are common kung fu training injuries?

Overuse chronic pain, accidental collisions with training partners, insufficient recovery time and underlying health issues can cause muscle, joint or ligament injuries if not careful.

Is kung fu safe for kids?

Children’s kung fu classes emphasize control, discipline and safety. Benefits include improved coordination, confidence, focus and conflict resolution skills.

Can I learn kung fu online?

Videos can offer inspiration but no digital media replaces in-person apprenticeship over sustained duration under an experienced Sifu to correctly guide nuanced practice.

Which kung fu style is most powerful?

No single style is objectively superior since each have distinct characteristics suiting different body types, temperaments and strategic contexts. Mastery comes through long term devotion.

What are common kung fu weapons?

Signature weapons in Chinese martial arts include straight sword (jian), broadsword (dao), staff (gun), spears (qiang), varieties of hooks, whips, fans and exotic bladed polearms.

Were nunchucks actually used as weapons?

Nunchaku (dual section staff) originated as rice flailing tools in Okinawa. Chinese adaptions emerged later when martial arts exported to Japan, but practical weapon usage remains contentious.

Can I learn kung fu from a book?

Books and instructional media can supplement personal training but no substitute for in-person apprenticeship model of continual feedback and accumulated wisdom of embodied practice traditions.

Where is the best place to learn kung fu?

Established academies in China or with verifiable lineage ties maintain authentic cultural heritage. But skilled instruction can exist globally. Discern teachers carefully through first-hand experience before committing long-term.

How do I choose a kung fu school?

Investigate credentials, teaching methods, safety protocols, costs and skill level of students. Ensure the teacher offers a traditional framework beyond just fitness while aligning with personal learning priorities.

What questions should I ask a potential kung fu teacher?

Their lineage and formal recognition as sifu. Training methods and modifications for individual needs. Injury prevention and recovery strategies. Teaching philosophy and general vibe to assess teacher-student suitability.

[…] Read Next on The Philosophy and Spiritual Aspects of Kung Fu: An Exploration of Qi/Chi, Yin & Yang and Buddhi… […]